Most historians agree that there is evidence of homosexual activity and same-sex love, whether such relationships were accepted or persecuted, in every documented culture.

Social movements, organizing around the acceptance and rights of persons who might today identify as LGBT or queer, began as responses to centuries of persecution by church, state and medical authorities. Where homosexual activity or deviance from established gender roles/dress was banned by law or traditional custom, such condemnation might be communicated through sensational public trials, exile, medical warnings and language from the pulpit.

These paths of persecution entrenched homophobia for centuries—but also alerted entire populations to the existence of difference. Whether an individual recognized they, too, shared this identity and were at risk, or dared to speak out for tolerance and change, there were few organizations or resources before the scientific and political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries. Gradually, the growth of a public media and ideals of human rights drew together activists from all walks of life, who drew courage from sympathetic medical studies, banned literature, emerging sex research and a climate of greater democracy.

By the 20th century, a movement in recognition of gays and lesbians was underway, abetted by the social climate of feminism and new anthropologies of difference. However, throughout 150 years of homosexual social movements (roughly from the 1870s to today), leaders and organizers struggled to address the very different concerns and identity issues of gay men, women identifying as lesbians, and others identifying as gender variant or nonbinary.

White, male and Western activists whose groups and theories gained leverage against homophobia did not necessarily represent the range of racial, class and national identities complicating a broader LGBT agenda. Women were often left out altogether.

We know that homosexuality existed in ancient Israel simply because it is prohibited in the Bible, whereas it flourished between both men and women in Ancient Greece. Substantial evidence also exists for individuals who lived at least part of their lives as a different gender than assigned at birth. From the lyrics of same-sex desire inscribed by Sappho in the seventh century BCE to youths raised as the opposite sex in cultures ranging from Albania to Afghanistan; from the “female husbands” of Kenya to the Native American “Two-Spirit,” alternatives to the Western male-female and heterosexual binaries thrived across millennia and culture.

These realities gradually became known to the West via travelers’ diaries, the church records of missionaries, diplomats’ journals, and in reports by medical anthropologists. Such eyewitness accounts in the era before other media were of course riddled with the biases of the (often) Western or white observer, and added to beliefs that homosexual practices were other, foreign, savage, a medical issue, or evidence of a lower racial hierarchy. The peaceful flowering of early trans or bisexual acceptance in different indigenous civilizations met with opposition from European and Christian colonizers.

In the age of European exploration and empire-building, Native American, North African and Pacific Islander cultures accepting of “Two-Spirit” people or same-sex love shocked European invaders who objected to any deviation from a limited understanding of “masculine” and “feminine” roles. The European powers enforced their own criminal codes against what was called sodomy in the New World: the first known case of homosexual activity receiving a death sentence in North America occurred in 1566, when the Spanish executed a Frenchman in Florida. Against the emerging backdrop of national power and Christian faith, what might have been learned about same-sex love or gender identity was buried in scandal.

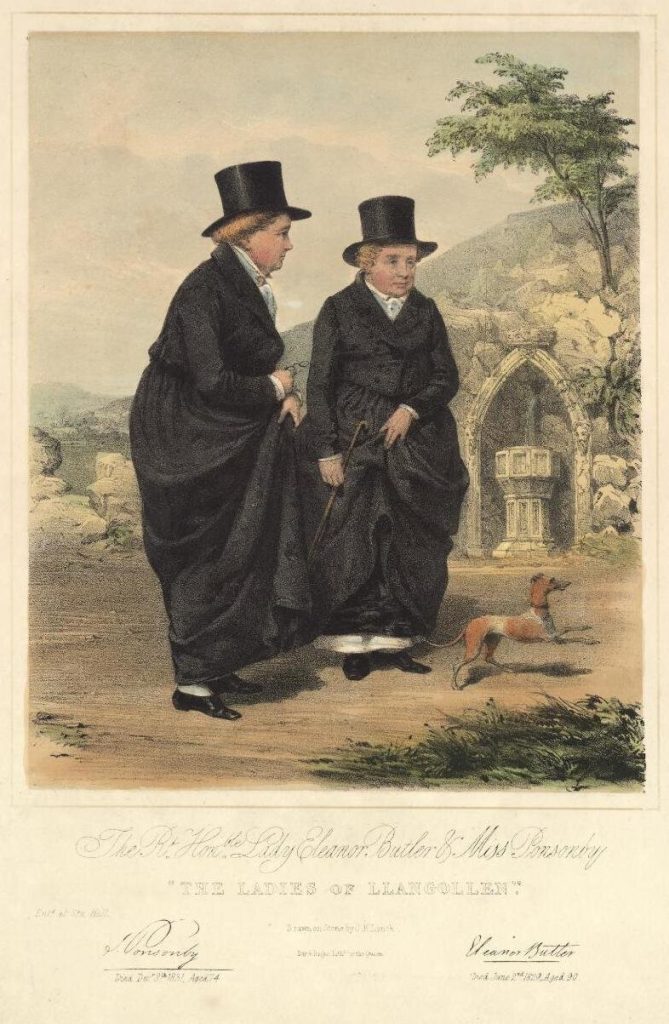

Ironically, both wartime conflict between emerging nations and the departure or deaths of male soldiers left women behind to live together and fostered strong alliances between men as well. Same-sex companionship thrived where it was frowned upon for unmarried, unrelated males and females to mingle or socialize freely. Women’s relationships in particular escaped scrutiny since there was no threat of pregnancy. Nonetheless, in much of the world, female sexual activity and sensation were curtailed wherever genital circumcision practices made clitoridectomy an ongoing custom.

Where European dress—a clear marker of gender—was enforced by missionaries, we find another complicated history of both gender identity and resistance. Biblical interpretation made it illegal for a woman to wear pants or a man to adopt female dress, and sensationalized public trials warned against “deviants” but also made such martyrs and heroes popular: Joan of Arc is one example, and the chilling origins of the word “faggot” include a stick of wood used in public burnings of gay men. Despite the risks of defying severe legal codes, cross-dressing flourished in early modern Europe and America. Women and girls, economically oppressed by the sexism which kept them from jobs and economic/education opportunities designated for men only, might pass as male in order to gain access to coveted experiences or income. This was a choice made by many women who were not necessarily transgender in identity.

Women “disguised” themselves as men, sometimes for extended periods of years, in order to fight in the military (Deborah Sampson), to work as pirates (Mary Read and Anne Bonney), attend medical school, etc. Both men and women who lived as a different gender were often only discovered after their deaths, as the extreme differences in male vs. female clothing and grooming in much of Western culture made “passing” surprisingly easy in certain environments. Moreover, roles in the arts where women were banned from working required that men be recruited to play female roles, often creating a high-status, competitive market for those we might today identify as transwomen, in venues from Shakespeare’s theatre to Japanese Kabuki to the Chinese opera. This acceptance of performance artists, and the popularity of “drag” humor cross-culturally, did not necessarily mark the start of transgender advocacy, but made the arts an often accepting sanctuary for LGBT individuals who built theatrical careers based around disguise and illusion.

SEXOLOGY

The era of sexology studies is where we first see a small, privileged cluster of medical authorities begin promoting a limited tolerance of those born “invert.” In Western history, we find little formal study of what was later called homosexuality before the 19th century, beyond medical texts identifying women with large clitorises as “tribades” and severe punishment codes for male homosexual acts. Early efforts to understand the range of human sexual behavior came from European doctors and scientists including Carl von Westphal (1869), Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1882) and Havelock Ellis (1897). Their writings were sympathetic to the concept of a homosexual or bisexual orientation occurring naturally in an identifiable segment of humankind, but the writings of Krafft-Ebing and Ellis also labeled a “third sex” degenerate and abnormal.

Sigmund Freud, writing in the same era, did not consider homosexuality an illness or a crime and believed bisexuality to be an innate aspect beginning with undetermined gender development in the womb. Yet Freud also felt that lesbian desires were an immaturity women could overcome through heterosexual marriage and male dominance. These writings gradually trickled down to a curious public through magazines and presentations, reaching men and women desperate to learn more about those like themselves, including some like English writer Radclyffe Hall who willingly accepted the idea of being a “congenital invert.” German researcher Magnus Hirschfeld went on to gather a broader range of information by founding Berlin’s Institute for Sexual Science, Europe’s best library archive of materials on gay cultural history. His efforts, and Germany’s more liberal laws and thriving gay bar scene between the two World Wars, contrasted with the backlash, in England, against gay and lesbian writers such as Oscar Wilde and Radclyffe Hall. With the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich, however, the former tolerance demonstrated by Germany’s Scientific Humanitarian Committee vanished. Hirschfeld’s great library was destroyed and the books burnt by Nazis on May 10, 1933.

In the United States, there were few attempts to create advocacy groups supporting gay and lesbian relationships until after World War II. However, prewar gay life flourished in urban centers such as New York’s Greenwich Village and Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. The blues music of African-American women showcased varieties of lesbian desire, struggle and humor; these performances, along with male and female drag stars, introduced a gay underworld to straight patrons during Prohibition’s defiance of race and sex codes in speakeasy clubs. The disruptions of World War II allowed formerly isolated gay men and women to meet as soldiers and war workers; and other volunteers were uprooted from small towns and posted worldwide. Many minds were opened by wartime, during which LGBT people were both tolerated in military service and officially sentenced to death camps in the Holocaust.

This increasing awareness of an existing and vulnerable population, coupled with Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s investigation of homosexuals holding government jobs during the early 1950s outraged writers and federal employees whose own lives were shown to be second-class under the law, including Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Allen Ginsberg and Harry Hay. Awareness of a burgeoning civil rights movement (Martin Luther King’s key organizer Bayard Rustin was a gay man) led to the first American- based political demands for fair treatment of gays and lesbians in mental health, public policy and employment. Studies such as Alfred Kinsey’s 1947 Kinsey Report suggested a far greater range of homosexual identities and behaviors than previously understood, with Kinsey creating a “scale” or spectrum ranging from complete heterosexual to complete homosexual.

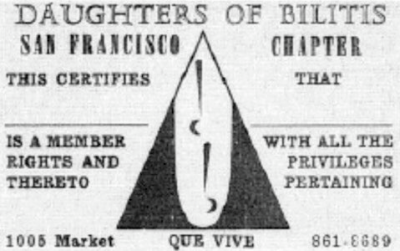

The primary organization for gay men as an oppressed cultural minority was the Mattachine Society, founded in 1950 by Harry Hay and Chuck Rowland. Other important homophile organizations on the West Coast included One, Inc., founded in 1952, and the first lesbian support network Daughters of Bilitis, founded in 1955 by Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin. Through meetings and publications, these groups offered information and outreach to thousands.

These first organizations soon found support from prominent sociologists and psychologists. In 1951, Donald Webster Cory published “The Homosexual in America”, asserting that gay men and lesbians were a legitimate minority group, and in 1953 Evelyn Hooker, PhD, won a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to study gay men. Her groundbreaking paper, presented in 1956, demonstrated that gay men were as well-adjusted as heterosexual men, often more so. But it would not be until 1973 that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality as an “illness” classification in its diagnostic manual. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, gay men and lesbians continued to be at risk for psychiatric lockup as well as jail, losing jobs, and/or child custody when courts and clinics defined gay love as sick, criminal or immoral.